The Inheritance, London's Epic, 7-hour “Play of the Century” Arrives on Broadway

“ONLY CONNECT!” Edward Morgan Forster writes in Howards End, his enduringly powerful 1910 novel about class, morality, and love in Edwardian England; “only connect the prose and the passion, and both will be exalted, and human love will be seen at its height.” In this line, the humanist Forster suggests the importance of linking what he describes as the “Inner life” and the “Outer life”: surface and depth, public image and private self. His book’s complex and vividly drawn characters are defined by their abilities to make these bridges, by their respective levels of hypocrisy, empathy, or compassion.

Clockwise from top left: The Broadway cast of The Inheritance includes Dylan Frederick, Carson McCalley, Jonathan Burke (seated, with book), John Benjamin Hickey (standing, in suit), Samuel H. Levine, Andrew Burnap (in sunglasses), Darryl Gene Daughtry Jr. (on floor), Arturo Luís Soria (crouched), and Kyle Soller (seated). Sittings Editor: Phyllis Posnick. Produced by LOLA Productions. Set design, Jesse Kaufmann. Photographed at Seret Studios. Photographed by Steven Klein, Vogue, November 2019

But in playwright Matthew Lopez’s eviscerating and entirely absorbing new work, The Inheritance, the iconic line takes on an additional layer of meaning. The two-part, seven-hour play deftly connects Forster’s novel to a pan-generational queer milieu in contemporary New York, effectively proving the timelessness of the novelist’s themes.

The play shattered audiences in a sold-out run at London’s Young Vic when it premiered in March 2018; The Guardian’s Michael Billington praised director Stephen Daldry’s “crystalline production” and noted that the play “pierces your emotional defenses, raises any number of political issues and enfolds you in its narrative.” Before its transfer to the West End’s Noël Coward Theatre, it was lauded by The Telegraph’s Dominic Cavendish as “perhaps the most important American play of the century so far.” It was subsequently garlanded with awards (the Evening Standard’s Best Play, the Olivier for Best Director).

Now The Inheritance, commandingly directed by Daldry and with several of the principal actors from the London production, has begun previews on Broadway at the Ethel Barrymore Theatre. With AIDS as a haunting presence, inevitable and favorable comparisons have been drawn with Tony Kushner’s game-changing 1991 epic, Angels in America. (Daldry and the show's designer, Bob Crowley, even give one of their characters prop-house wings in the London production.) But it is Forster’s novel that primarily informs Lopez’s new work. “Whenever we hit a roadblock in a workshop,” he says, “the answer was very often to be found in Howards End.”

Lopez makes Forster himself—he goes by “Morgan”—a central character. A donnish, avuncular figure in buttoned-up tweeds, Morgan, at the play’s inception, is instructing a group of young men on the art of transferring life experience to paper. This circle of friends, serving as a kind of Greek chorus, questions Morgan about the seemingly effortless elegance of his book’s opening line—“One may as well begin with Helen’s letters to her sister”—so “dashed off, as if to suggest it doesn’t really matter how you start,” one of them comments. “One may as well begin with Toby’s voicemails . . . to his boyfriend,” they conclude. And so it begins.

A closeted man from an age that criminalized homosexuality, Morgan (played by Paul Hilton) is filled with wonder at this younger generation, a tribe of unencumbered men able to live their individual truths buoyed by preternatural self-awareness, PrEP (the daily preventative HIV medication), and pop-culture drollery. What they are often less aware of, as they navigate the travails of Manhattan real estate, Hamptons house parties, and nightclub dark rooms, are the struggles of a preceding generation that fought for liberation and was decimated by the early years of the AIDS holocaust in the 1980s. “How can we learn from the past to forge a greater future together?” queries actor Kyle Soller, who plays Eric Glass, an earnest activist. “It’s just such a universal, human story about how we need to recognize our collective history: There’s a message I think we really need right now.”

At the outset of the play’s action, Toby Darling (a lost-boy playwright, electrifyingly played by Andrew Burnap) is living in a spacious, rent-controlled Upper West Side apartment, the childhood home of his fiancé, Eric. Forster’s novel revolves around an inheritance, the romantic country house (Howards End) bequeathed by the mystical Ruth Wilcox to the freethinking Margaret Schlegel, a mere acquaintance whom she nevertheless recognizes as a kindred spirit. In The Inheritance, it is a house upstate that decades earlier the young lovers Henry and Walter intended as a refuge from the disease that was ravaging their circle of friends and that is destined to become a sanctuary of a different sort.

Lopez had a “thwarted inheritance” of his own. Raised in Panama City, “a small town in the part of the Florida panhandle known,” he says, “as the ‘Redneck Riviera,’ ” he yearned for the Brooklyn of his parents’ childhoods. “I think they must have seen in it a kind of paradise,” he continues. “My dad was raised in housing projects; now they’re able to own a home and land.” Their son, however, did not see northwestern Florida as a paradise. “It was baffling to me.” (He has now reclaimed his parents’ urban roots, living in Brooklyn with his husband of four years, Brandon Clarke.) “The solace I had—besides my parents, who were loving and caring—was the movies and theater and reading,” he recalls. “The local community theater was my salvation.”

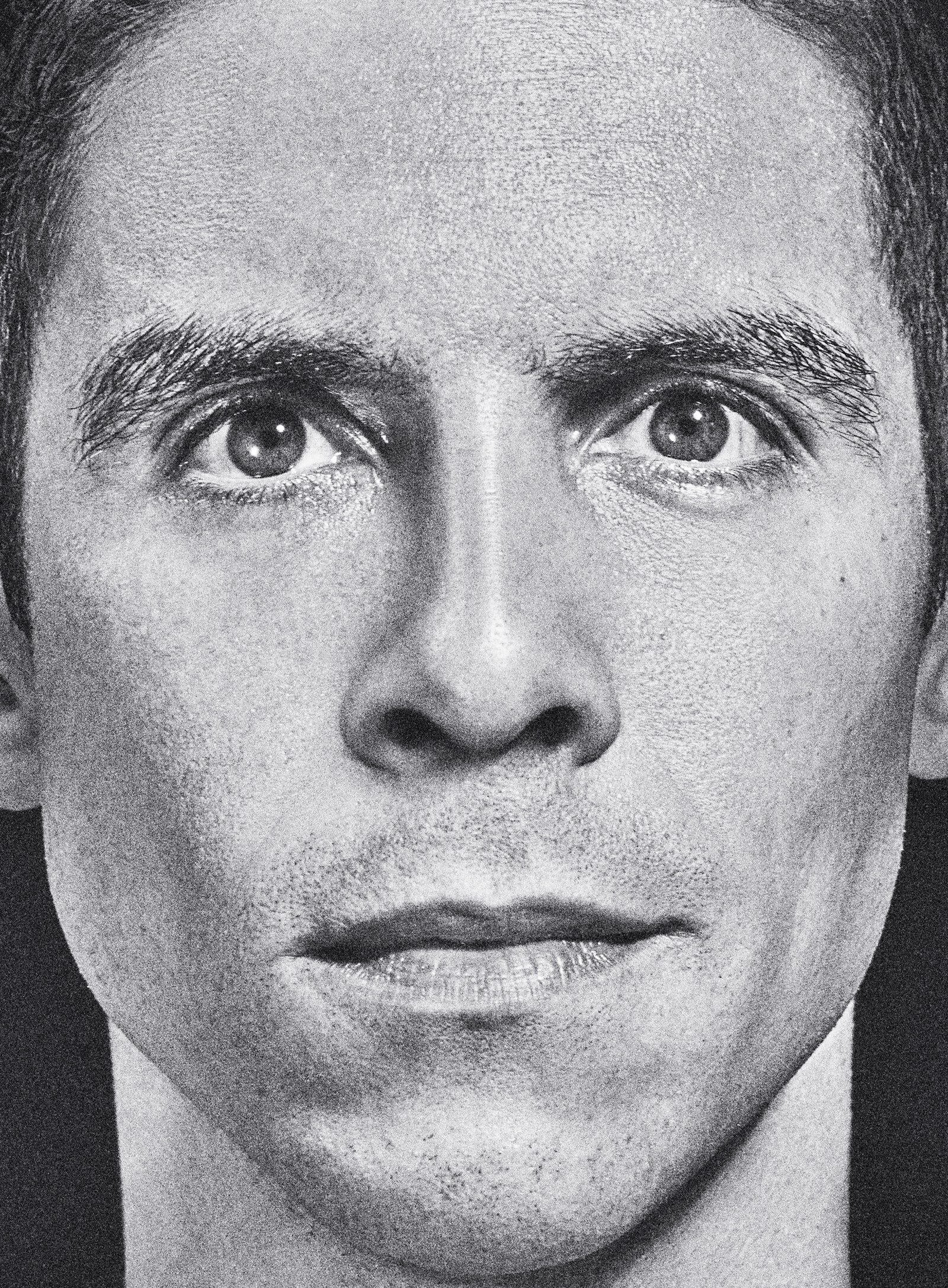

"A play is theoretical until you actually get it on its feet,” says Lopez, pictured here. In this story: hair, Thom Priano for R+Co. Haircare. Photographed by Steven Klein, Vogue, November 2019

The teenage Lopez saw Ismail Merchant and James Ivory’s powerful 1992 adaptation of Howards End. “I knew nothing about E. M. Forster. I knew nothing about Howards End,” he remembers, “but seeing that movie absolutely changed my life. It was the first thing that really struck a chord with me as a writer. I was just so enamored of the film and then later the book—and the love affair has not abated.” The 1987 movie adaptation of Forster’s homoerotic Maurice, published only after the writer’s death in 1970, was to prove a further revelation, although Lopez had to seek this one out. “They were not showing it in Panama City; that’s for sure,” he says, laughing, “and it was not available at the local Blockbuster.” When he finally watched the film and then researched Forster’s life, he recalls thinking, “Holy shit, this is Howards End but gay!” The revelation gave Lopez “the notion of retelling Howards End as a queer story,” and six years ago the writer (who won acclaim for his 2006 breakout play The Whipping Man) set out to “re-investigate” the book. Lopez wrote every word of his original draft at a Brooklyn writers’ space, often working until three in the morning and even on Christmas Eve.

The result, as Andrew Burnap discovered during one of four major workshops that spanned two years, was “a beautiful mess” that ran some 10 hours. Burnap had been starring as a sad-sack Elvis impersonator turned stellar drag queen in Lopez’s comedic play The Legend of Georgia McBride in Los Angeles but knew nothing about the new play until his manager sent him the script. “I read it at night,” he recalls. “I started at nine and finished at six. For the sake of my roommates, I was trying to keep the weeping to a dull roar and muffle the laughing as well—because I also found it wildly funny.”

During the workshop, Burnap played one of the young men in the circle of friends, but he was eventually asked to step in and play the part of Toby. “I even told him, ‘You’re too young for the role, but you’d be doing me a huge favor,’ ” Lopez recalls. Months later, Burnap got a call while he was driving in L.A. “I pulled over and sort of felt that my life was about to change,” he remembers. Burnap had never been to Europe before he traveled for the play; the new production will mark his Broadway debut.

His fellow cast member Kyle Soller received the 400-page script the day before his audition. Undaunted, he finished reading it on the subway en route to the audition. “I felt there was something special in my hands,” Soller recalls. “The characters are so fully formed and three-dimensional, and Matthew’s writing is heartbreaking and poetic in equal measure.” (Soller’s performance won him both the Olivier and Critics’ Circle Theatre Award for Best Actor.)

“It was something that hits you like a ton of bricks,” says actor Samuel H. Levine of Lopez’s writing. (The actor admits that he “had no idea” who Forster was when he embarked on The Inheritance. “Now I feel like I know him,” he says.) Levine plays both Adam, a young actor on a blazing meteor’s arc, and Leo, a hustler on the reverse trajectory. Having dropped out of school, Levine was working in a restaurant when he was called in to do the workshop. “I thought, There’s no way in hell I am ever going to do this,” he recalls, “so let’s just let it rip,” and that unharnessed energy helped to secure him the dual roles of the very different characters. From those early stages, Levine remembers the constant flow of new pages. “We must have killed a lot of trees!”

“There was just more than we could ever stage,” Lopez admits of his first drafts. “A play is theoretical until you actually get it on its feet and watch it in a run. I don’t think those early audiences knew quite how much power they had,” he adds. “They taught us everything.” The first preview before a Young Vic audience proved, as Levine recalls, “overwhelmingly electric—it hit really hard, hearing the reactions.” Burnap remembers “sneaking into the back of the theater,” during the wrenching conclusion of act one, “and witnessing the sort of theatrical event where everyone’s life is changed, almost as if the entire audience is held in suspension,” he says. “I’m just so moved in every performance,” says Soller, “because we can hear the audience audibly crying, full of the histories that they’re bringing to the story.”

One member of the London cast who brought a particularly poignant past to the story was the legendary Vanessa Redgrave, who was a haunting Ruth Wilcox in the Merchant--Ivory movie and played a mother whose son has succumbed to AIDS decades earlier in The Inheritance. (The actress herself lost her ex-husband Tony Richardson, father of her daughters, Joely and the late Natasha Richardson, to complications from the disease in 1991.) Though Redgrave will not be appearing in New York, Lopez notes the power of her performance. “It was an incredibly humbling thing to watch her examine her own trauma and to see her put her personal experience in service of the play,” he says.

More changes are afoot in the new production—a new chorus and a subtle reconsidering. “With this new American ensemble comes a new personality,” Lopez says. “I think that the last thing we’re interested in doing is putting up a carbon copy of the production in London—otherwise, just show the video. One of the things that I learned from Stephen is always to question your assumptions, and always go with the desire to make it better.”

Thanks to the Forster estate’s supportive trustees, Lopez even visited the author’s rooms at King’s College, Cambridge University, and was able to study the writer’s original manuscripts. “I feel a different, newfound kind of kinship with Forster,” he says, “and I’d like to think that the cast came away feeling as possessive of Forster and his writing and his legacy as I was when I started writing the play.”