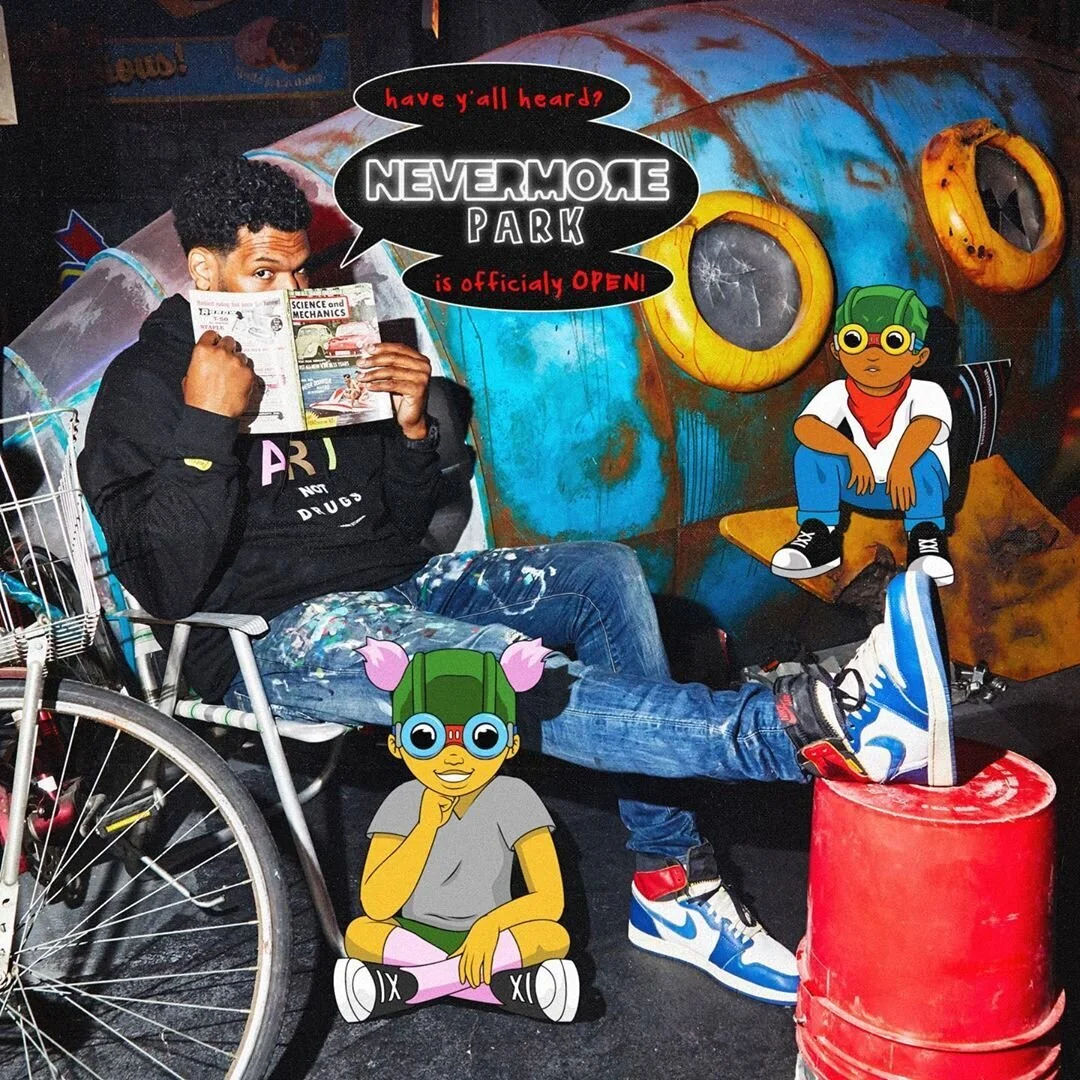

For Flyboys, Lil Mamas and Us: Hebru Brantley's Nevermore Park Imagines a Chicago Made for Dreamers

A pair of goggle-wearing kids from the South Side of Chicago may seem an unlikely set of superheroes, but artist Hebru Brantley’s “Fly Boy” and “Lil Mama” are exactly that. Chicagoans have become increasingly familiar with the comic-like duo in recent years as they’ve had a recurrent presence in Brantley’s art, which has appeared in both private and public spaces throughout the city and beyond.

Now, Flyboy and Lil Mama have a life-sized immersive universe to share with Chicago. The 6,000 square foot Nevermore Park, which opened in the city’s Pilsen neighborhood on Thursday, Oct. 24, is a reimagined glimpse of a beloved yet often beleaguered city. Built in partnership with Angry Hero and MWMu, with a build-out done by Iron Bloom Creative, Brantley tells The Root that Nevermore is meant to inspire the imagination within all of us.

“[Flyboy and Lil Mama] embody what it is to sort of dream and to imagine...to have that feeling—that sense that when you’re a kid, like there is limitless potential in the things that you can do and aspire to do,” says Brantley. “We kind of get that beat out of us as we get older, you know? I wanted to encapsulate that and give it sort of a sense of permanence within these characters...It was this idea that yesterday’s losers are today’s CEOs.”

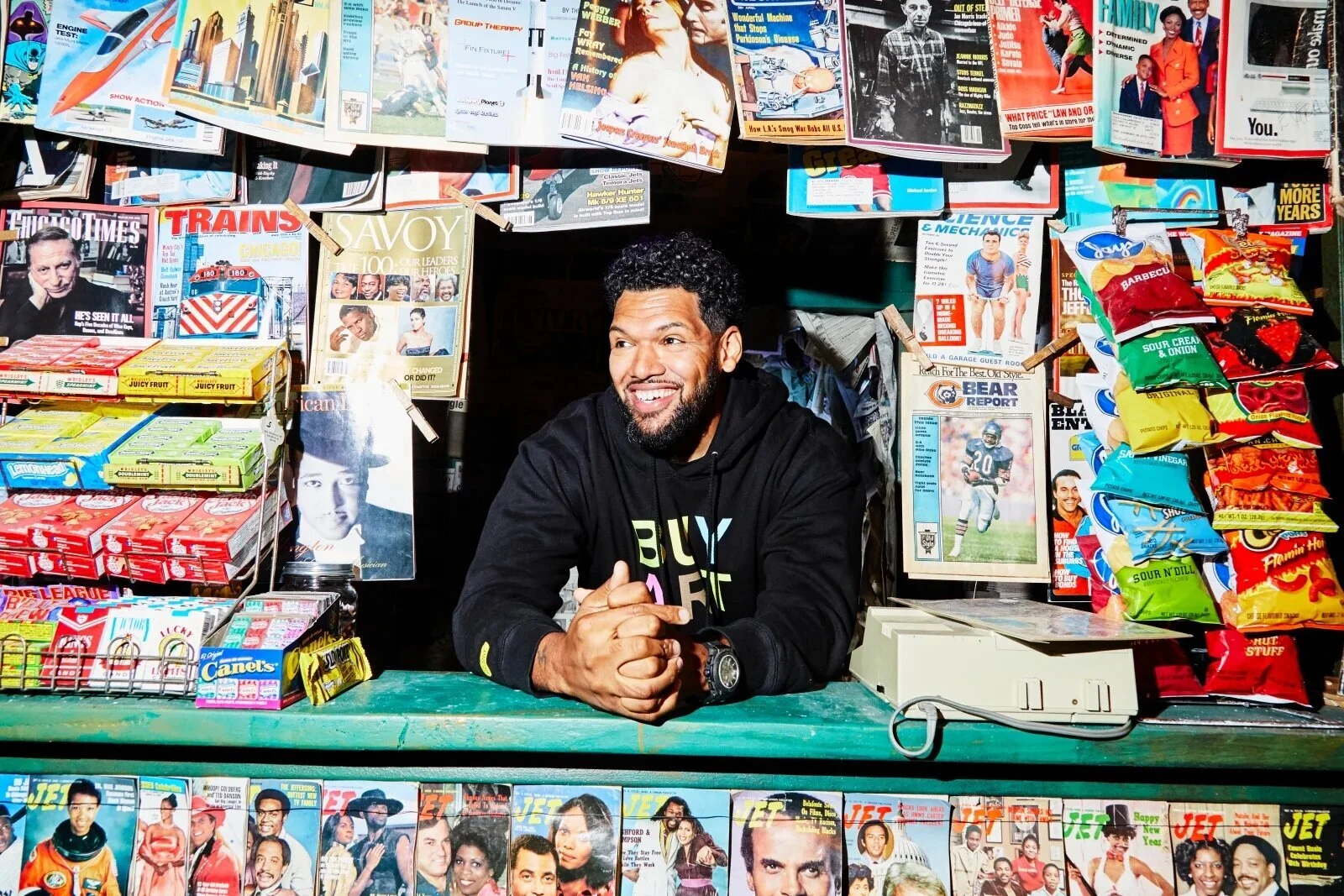

Growing up on Chicago’s South Side, Brantley admits his own creativity was often a well-guarded secret. Despite the city’s links to the AfriCOBRA movement and its now-thriving black art scene, in 1980s and ’90s Chicago (an era and city in which this writer was also coming of age), black boys weren’t expected to be into art.

“Given where I was from—given my ethnicity, given my height (Brantley is well over six feet)—there was an overwhelming assumption of who I was from the outside world,” he says, as he recalls hiding his artistic tendencies to avoid being ostracized by his childhood peers. “A black kid from the South Side of Chicago must be into sports [or] rap, and that was sort of it...not being allowed to have an imagination beyond those two things.”

“It’s different now, where social media has definitely given weight to art and artists being a thing that’s revered now, and it’s cool,” Brantley adds. “But when I was growing up, hell nah, that wasn’t cool...So, for me, my art was something I held very, very close to the chest.”

And yet, childlike wonder is alive and well in Nevermore Park, as are pieces of Brantley’s past—which he calls his “personal iconography.” Eagle-eyed viewers will catch subtle visual shoutouts to Ghostbusters, Wu-Tang, Jet and Savoy magazines and many other familiar bits of late 20th-century pop culture, as well as ample opportunities to mine their own imaginations and memory banks.

“I want people to feel as if they’re walking in one of my paintings,” says Brantley, citing the semi-animated, early ‘90s cult-classic film Cool World as one of his inspirations for Nevermore.

“Being able to walk through a painting and be in this space and in this world, it’s just visceral—and it’s intriguing for all ages...it’s an opportunity for us all to take a chill and a timeout, and remember a place where you didn’t have the worries or the stress,” he continues. “Everybody’s always trying to be so damned cool. Fuck the cool. Let’s just have fun and enjoy ourselves.”

Part of that enjoyment is rediscovering the wonder in America’s third-largest city—one that has been equally subject to gentrification and vilification as it continues to sift through its deep history of migration and subsequent segregation (notably, this year marks the 100th anniversary of the Chicago riots). While “Nevermore” may be a phrase initially identified with Edgar Allen Poe (via The Raven), Brantley tells us the word hit much closer to home.

“‘Nevermore’ was always a word that I was always kind of fascinated by because it was very contradictory,” he explains. “‘Never’ is finite—in the way of ‘no, never, ever again’; ‘more’ is plentiful—it’s adding to. I felt like that was a representation of the South Side of Chicago, in a way.”

For those of us with a history in the city, Brantley’s sentiment is all too familiar, as is his frustration with the “fake beautification of Chicago,” which has historically primarily meant the city’s downtown area. Of course, that frustration also applies to the city’s allocation of educational and developmental funds, which, like many cities, has often left out its most marginalized communities. (As this goes to press, the city is in the midst of a teachers’ strike; notably, the Chicago Teachers Union reports that over 80 percent of public school students affected by school closings and lack of resources are black.)

“On a surface level, [Nevermore Park is] an extremely fun, engaging, interactive experience—it could be easily just an Instagrammable moment for people,” says Brantley. “[But] looking into the detail, and kind of understanding Chicago’s political history—Chicago’s history—and then, from a revisionist history standpoint, stepping back and looking at sort of the ‘What if?’ of it all within this installation.”

As Brantley reveals, part of the “what if” is identifying the role models in our midst. The visual artist, who originally studied to be a filmmaker, cites rare black icons like Spike Lee as his examples of what was possible. But his own artistic education was far more organic; often through his own neighborhood.

“I learned who MLK, and Malcolm X, and Marcus Garvey were through murals. I learned who the Black Panthers were through murals; through this artistic expression,” he says. “I’m not saying that’s how every kid learns, but when you stifle that, when you set up obstacles to now block artistic expression from happening in a public arena in low-income neighborhoods, I think we kind of see the results, right?... I do believe it’s all relative, and it all plays a part.”

Of course, today’s Chicago is a hotbed of artistic expression. In addition to birthing artists like Common, Kanye West, Virgil Abloh and Chance the Rapper, the city boasts numerous visual artists—Theaster Gates, Amanda Williams, Torkwase Dyson, Dawoud Bey and Kerry James Marshall, among them—who continue to invest in Chicago by living and working here. The evolution has not been lost on Brantley, who hopes to be part of the next wave of Chicago’s artistic renaissance.

“I really, wholeheartedly believe that engaging with youth at an age where their minds are just like—not only sponges, but they’re activated on another level, because they’re not dealing with so much bullshit in the world—it hasn’t taken fully taken that thing from them yet,” he says. “The world moves because of creatives; it moves because of people who think ‘outside of.’ These are the innovators and these are the people who shape society. And so, for me, [that’s] what I want for Chicago...finding out ways to get the arts back, to be a champion for the arts in my city. I know my city is full of talented folks; more of us need to shine; more of us need to be the voice; more of us need to be the outliers.”

But while Nevermore Park may appear to be a showcase for Chicago’s youth, Brantley assures us it’s for anyone looking to recapture the magic of possibility.

“Be okay and unafraid and uninhibited to dream. It’s okay to imagine; it’s okay to want to express yourself and explore potential talents and reach for that creative voice,” he says. “I think it’s just about allowing people to engage.”

Entrance to Nevermore Park, at 949 W. 16th Street in Chicago, is open through Dec. 1. Tickets are available here.